Stories of Kiosks (Past and present of Shaumiani)

by Ketevan Lapachi & Lala Iskandarli

Illustrations and Photos by Lala Iskandarli

The work is the result of the summer school Researching Common Territories, which took place in the beginning of September in Marneuli, Kvemo Kartli, Georgia. It focused on Shaumiani, a village in Marneuli Municipality entirely inhabited by Armenians, with the exception of the former military town, where Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) from the Tskhinvali region live. Until 1925, Shaumiani was called Shulaveri, but because of changing the political system in the country, i.e. the formation of Georgian Soviet Socialist Republic (SSR) in 1921 (Jones, 1988, 616), it was renamed after Bolshevik revolutionary Stepan Shahumyan. Shaumiani was quite a big and important settlement during the Russian Empire and Soviet times. In 2014, however, it lost the status of daba (small town) and became a village. At that time, its population consisted of 3107 persons.[1]

[1] Statistical Yearbook of Georgia, National Statistics Office of Georgia, Tbilisi, 2014. p.38, https://www.geostat.ge/me- dia/20935/Yearbook_2014.pdf, (accessed, 29.10.2022).

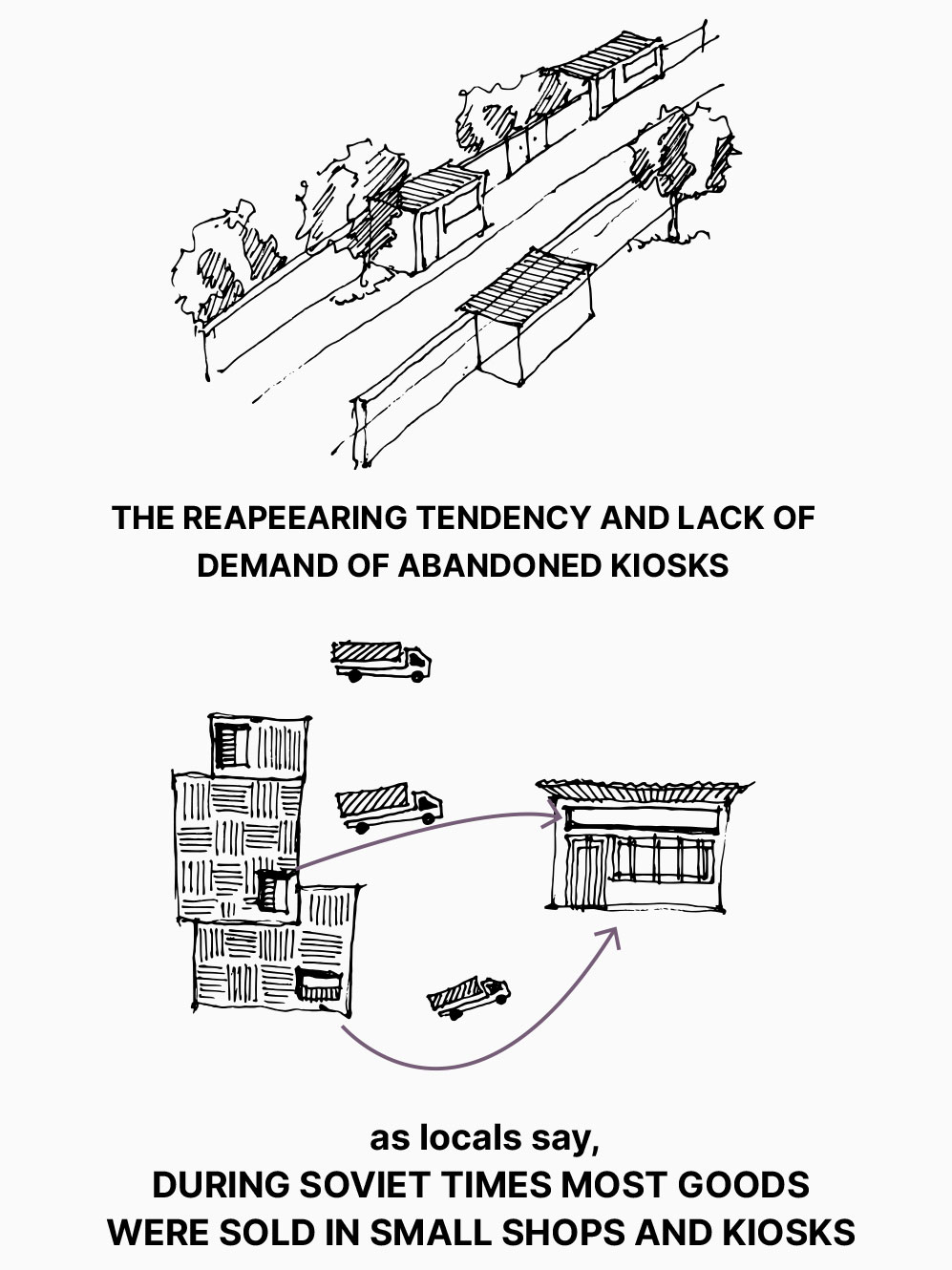

While walking along the main road in the so-called Armenian part of Shaumiani, we encountered a significant number of abandoned kiosks. The reappearing frequency of the kiosks and their lack of operations was something that truly caught our attention and brought us to the main theme of our research: self-sufficiency of the village during Soviet times and its present dependency.

The kiosks might be considered an infrastructure of the village that created the space and possibility for locals to exchange ideas and goods (Larkin, 2013, 328). An infrastructure itself is characterized by temporality and often perceived as an invisible background (Edwards, 2003, 191) that might become visible just after its disappearance. This may be partially true for Shaumiani since the kiosks drew our attention precisely because of their non-functionality. They seemed to have fallen out of space and time and no longer belonged to Shaumiani’s modernity. This research is based on non-participant observation and the interviews conducted with locals with the help of our translator, Vani Aslikyan. The shared stories and memories about kiosks acted as channels towards a broader understanding of past and present of Shaumiani.

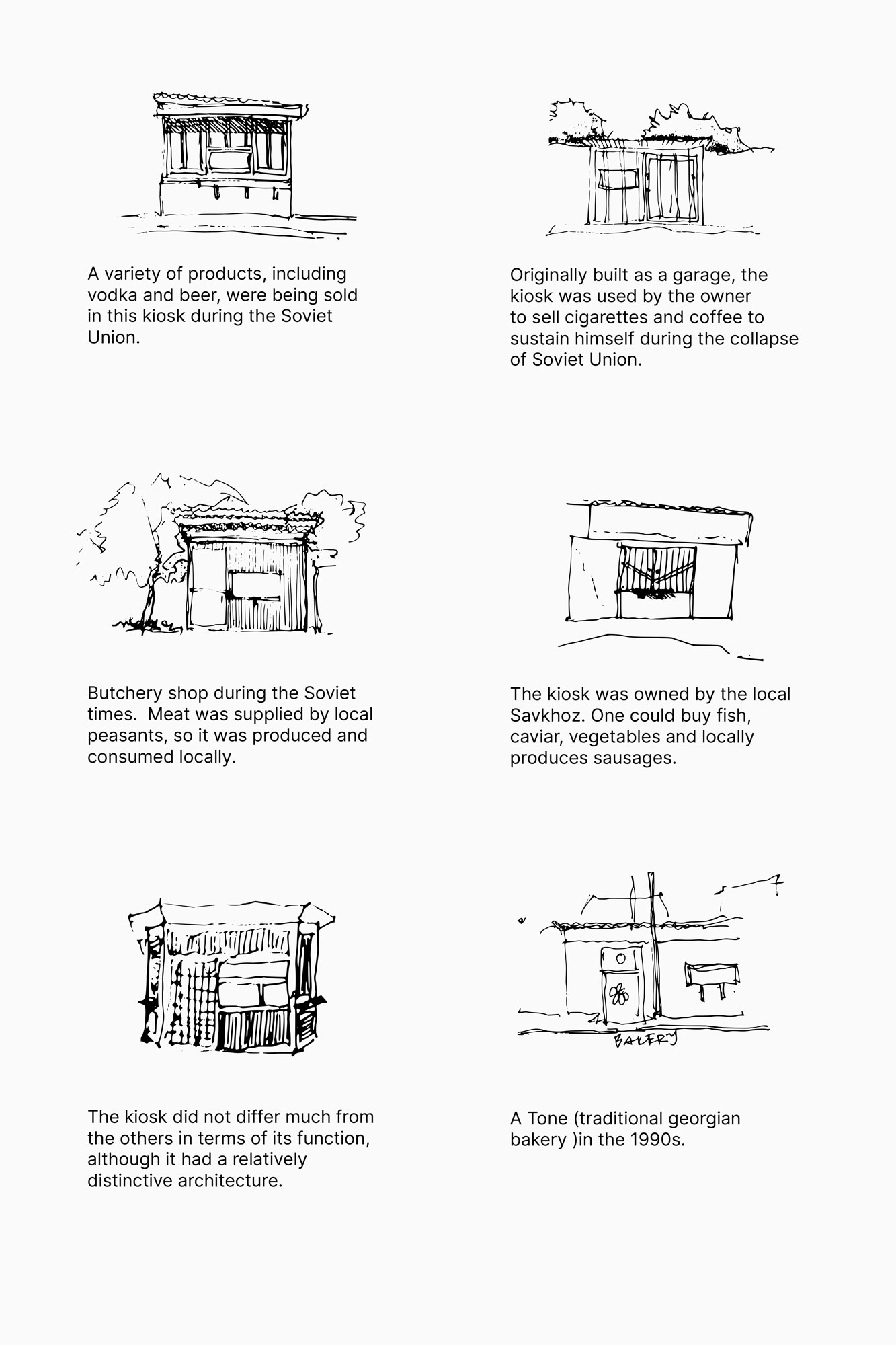

As locals told us, during Soviet times most of the consumer goods were being sold in different small shops or kiosks located along the main road of the village. There were kiosks for meat, fish, pastry, alcohol and most of them were selling an array of products, not only certain types of goods.Back then, Shaumiani also had grape growing Sovkhoz. In fact, grape growing was one of the leading undertakings of the Sovkhozs in the Georgian SSR. [2] Sovkhoz was a form of enterprise in the USSR that implemented private-in-the-collective economic principles (Konstantinov, 2007, 4). Workers of the Sovkhoz were paid wages, but they might have also cultivated personal garden plots (Ibid).

During our time in Shaumiani, inhabitants of the village mentioned that it was local residents who used to supply kiosks with meat, vegetables, fruits and some of the alcoholic drinks, thanks to the existence of the Shaumiani Sovkhoz. There were three butcher shops in Shaumiani and if a butcher wanted to buy meat, he would go to one of the residents of the village who had an animal farm. In fact, goods produced in the village were often consumed locally. However, nowadays Shaumiani is dependent on Marneuli and other big settlements around it. Local shop owners or residents themselves go to Marneuli or Tbilisi, sometimes even to Kakheti to buy products for everyday use, and many of the goods are imported from Russia.

Hence, kiosks have lost their original infrastructural significance and under consumer-focused capitalism, people in Shaumiani have less access to goods locally. The loss of locally produced and sold goods could be a reason for Shaumiani’s ever decreasing population since the collapse of the Soviet Union. Further, the history of kiosks in Shaumiani challenges the wide-spread notion that living under socialism meant living with a shortage of products. Today, theoretically, inhabitants of Shaumiani can buy anything from any part of the world. In reality, however, they have less access to goods locally than they did in Soviet times.

[2] Kakhniashvili J. Georgian Soviet encyclopedia, Vol 8, p. 582.

References:

Edwards PN. 2003. Infrastructure and Modernity: Force, Time and Social Organization in the History of Sociotechnical Systems, In Modernity and Technologies, ed. TJ Misa, P Brey, pp.185-225, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Jones S. 1988. The Establishment of Soviet Power in Transcaucasia, The Case of Georgia 1921-1928, Soviet Studies, Vol 11, No 4, pp. 616-639.

Konstantinov Y. 2007. Reinterpreting the Sovkhoz, Sibirica, Vol 6, No 2, pp.1-15.

Larkin B. 2013. The Politics and Poetics of Infrastructure, The Annual Review of Anthropology, Vol 43, pp. 327-347.

Read more:

IN THE SEARCH FOR COMMON NARRATIVES

by Klaudia Kosicińska

TRACING COMMON SPACES

by Corten Perez-Houis, Kirill Repin, Sopiko Rostiashvili, Marie-Luise Schega & Hermine Virabian

“YOURS, SPACE”

Poem by Marie-Luise Schega & Film Stills by Hermine Virabian

SUPRA OF STORIES

by Jan Chrzan, Katya Krat & Nutsa Lomsadze

SHULAVERI

by Natavan Alieva

The Sevda of Sadakhlo

by Ana Kvichidze, Catherine Steiner & Klara Böck

THE LIBRARY OF SHAUMIANI

by Juri Wasenmüller